Yeah, you know what I mean.

Yeah, you can go ahead and cringe. If you're squeamish, you may just want to go ahead and visit now, 'cause this is downright uncomfortable to talk about.

The fracture of the penis.

How

does it happen? As you might expect: the erect penis does not actually

have a whole heck of a lot of weight-bearing capacity. So, when a man or his partner should happen to drop their weight onto

the penis on its longitudinal axis, it cannot support the weight and it

begins to flex. The problem: when the penis is erect,

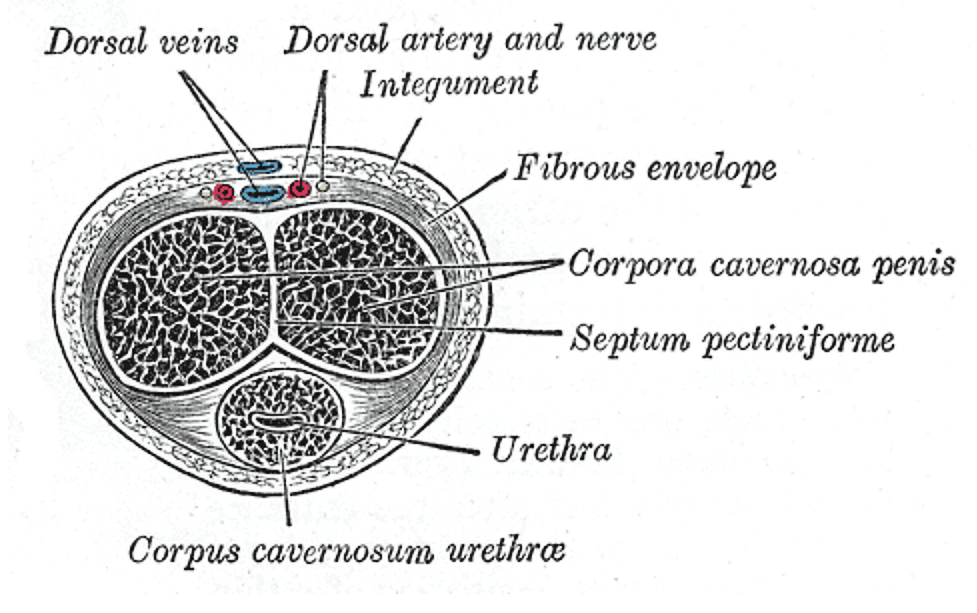

it's sort of an inflated tube under pressure, with a tough, fibrous

capsule to contain the pressure and give it shape. This is called the

tunica albuginea. It's not very flexible, or the penis would just keep

getting bigger and would never get hard. When the penis is fully

erect, the fibers are stretched more or less to their limit. And when

the erect penis is forcibly bent, the fibers on the outside portion of

the bend may tear.

So we call it a "fracture" because that's

what it looks like, but it's more precisely described as a

tear in the fibrous envelope that is the tunica albuginea.

The surgery is not for the faint of heart, either. It involves (take a deep breath before reading the next phrase) degloving the skin of the penis in order to evacuate the hematoma and to access the site of injury to repair it.

So recently I saw an unhappy young man with such an injury. It was sustained in the usual manner, but it was in fact the mildest one I have ever seen. The hematoma was not large and the angulation of the injured member was slight. I thought it was clearly a fracture, but the urologist who examined the patient was uncertain, and the patient, understandably, was quite unwilling to undergo surgery if the diagnosis was unclear. We discussed diagnostic options. Ultrasound apparently has a low sensitivity, but, the urologist had read, . I did not know that. So I proceeded to order the first and only MRI of the penis of my entire career. After an incredulous phone call from the radiologist to confirm the order, we obtained the following images.

This is the "money shot," if you'll excuse the phrase. A transverse image, catching the penis in two sections as it curves down. The resolution of this is lovely, and the anatomy is vivid. The twin corpora are sharply delineated, and the fascia of the tunica is obvious, as is the small tear indicated by the arrow. You can even see the communication of the blood between the corpus and the hematoma! What a wonder technology is.

This is not something I expect is commonly seen. After all, this is almost always a clinical diagnosis, and the only diagnostic study needed may be a retrograde urethrogram to ensure that the urethra is intact. But it's useful to know that there is an option if it is needed.

This case also has a happy ending. The surgery went well -- with such a small injury it was an easy repair -- and as of this time, the patient seems to have made a full recovery.